The president of El Corte Inglés, Europe’s biggest department store by sales, is struggling to cling to power amid an escalating battle between two sides of its powerful and politically connected founding family that insiders say is starting to resemble a telenovela soap opera.

A special board meeting is expected in the coming weeks to discuss removing Dimas Gimeno as president after four years, potentially replacing him with his cousin and rival Marta Álvarez, according to six people with knowledge of the situation. At least seven of the 10 board members are set to vote against him, according to these same people.

A meeting was held on Wednesday, where the accounts for last year were signed off — and seven board members supported the call for the extraordinary meeting, as well as refusing to consider a number of proposals by the president. “It’s over for [Mr] Gimeno,” said one senior official at the company. “He has lost the support of the board.” El Corte Inglés declined to comment. Mr Gimeno declined to comment. One person close to him, however, admitted that he was fighting for his survival as president. “It is not over until it’s over, but Gimeno is in a tough spot.” Analysts say that if Mr Gimeno is ousted, the ensuing turmoil could slow the pace of reform within the group, which is struggling with sluggish growth and a high debt load a time when traditional retailers — and particularly department stores — are under huge pressure from nimble online operators such as Amazon or fashion group Asos.

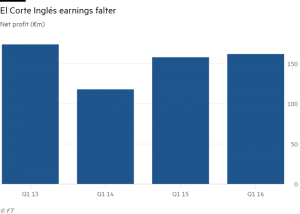

For the financial year from March 2016 to February 2017, the last available numbers, El Corte Inglés reported that sales and net profits rose 2 per cent to €15.5bn and €161m, respectively. The group’s net debt stands at €3.7bn. “The business model of El Corte Inglés is quite old fashioned,” said Ricardo Wehrhahn, managing partner at consultancy Intral Strategy Execution, adding that it needs to discuss expansion abroad, develop a stronger online service and provide a better offering for millennial consumers. “The clock is ticking for traditional retailers and they do not have time to lose with these kinds of internal struggles.”

Privately held El Corte Inglés (“The English Cut”) has long been one of Spain’s largest and most influential companies, with a department store in nearly every major town as well as hypermarkets, opticians, convenience stores, travel agents and DIY centres. Employing more than 90,000 workers across 1,400 sites, only the state has more people on its payroll in the country. For a quarter of a century, until he died in 2014, El Corte Inglés was dominated by one man: Isidoro Alvarez, nephew of the company’s founder Ramón Areces. On Alvarez’s death, his favourite nephew — who had been groomed for the job — replaced him as executive president. But control of his 22 per cent stake in El Corte Inglés went to his two daughters Marta and Cristina Álvarez. The problem, say people close to the company, is that the two sides of the family have never got on. “There was never much love there,” said one person close to the family. Relations have deteriorated even further since the death of Alvarez, with several complaints lodged in the courts in a dispute over inheritance. “The conflict is starting to resemble a [Latin American] telenovela,” said one senior figure in the company.

Critics of Mr Gimeno within El Corte Inglés say the family dispute is only half the story, pointing out that other board members are planning to vote against him as well as Marta and Cristina. They allege poor management on his part, saying he was unable to maintain the support of the board or deliver major reforms. In October, he was stripped of his executive powers, which were ceded to two chief executive officers. “The truth is, we have lost time with Gimeno,” said one opponent in the group. But another story is that beyond family politics, conservative forces within El Corte Inglés have been resistant to Mr Gimeno’s attempts to instil 21st century standards of governance at the private company — with one eye on preparing it for an eventual public listing.

Mr Gimeno pushed for EY to audit the group’s security department amid allegations of irregularities. The report has not yet been released, but the investigation has caused upset within the group. He helped bring in foreign capital in the form of Qatari Sheikh Hamad bin Jassim bin Jaber Al Thani. He also wanted to introduce more independent board members, say his allies. “There are people in El Corte Inglés who want the company to run like it did in the 20th century, but that is impossible,” said one ally of Mr Gimeno. “He wanted to modernise the group, but he has been prevented.”

Analysts say the power struggle comes at a challenging time for the company in an industry that is changing rapidly. José L Nueno, professor in the marketing department at IESE, said El Corte Inglés has had successes in recent years, reducing costs as well as improving its food and home furnishings business. But at the same time it “has been very slow to adapt digitally” and now needs to now focus on improving its performance online as well as dealing with its unprofitable stores and its weak fashion offering. He said that whatever the outcome of the power struggle, it will take time: “El Corte Inglés is a supertanker, so fast change is hard.”

Published by Michael Stothard in Madrid for The Financial Times in June